Changing perceptions

A driving force behind the Watch and Grow community group in Coalburn, South Lanarkshire, Cairns Galbraith has worked hard alongside fellow volunteers to raise awareness of the growing nature in and around this former mining village.

Projects have included the improvement of a nature trail in the village, the building of what is now a much-loved community bird hide and a number of other small-scale initiatives designed to connect local residents with nature and the outdoors.

Cairns was a participant in the first cohort of the Scottish Wildlife Trust’s Nextdoor Nature Pioneers Programme – an experience that helped equip him with additional skills with which to progress further ambitious plans for the village, involving even more local groups and residents.

Average reading time: 10 minutes

WATCHING footage recorded overnight on a trail camera, one little girl couldn’t contain her excitement: “We have wolves at the bottom of our garden!” she cried.

Her mum had accepted an offer of having a camera installed to learn more about the wildlife that came and went in their garden while the curtains were drawn and the human residents were asleep inside. The wolves were actually foxes, but no matter! Much more importantly, engagement had begun and a seed of interest sown.

The man behind the trail cam – and a host of other initiatives throughout the village – is Cairns Galbraith, who moved to Coalburn in 2019. A keen hillwalker, gardener and wildlife photographer, Cairns has long had a love of the outdoors, with each of his interests feeding the other. Soon after he moved to the village, Cairns was invited to join a community group called Watch and Grow Coalburn that was formed as a means for its 1,200 or so residents to share ideas and experiences around gardening and wildlife during the first lockdown. With an awareness of just how shut away some in the community had become, the group wanted to keep residents engaged and occupied during such an unsettling time.

Watch and Grow subsequently developed a community page on Facebook, which Cairns used to enquire locally about who might like to help highlight the amount of nature that is all around. “I asked who would be interested in me putting out some food and setting up a trail camera in gardens to see what came foraging in the night,” he remembers. “At the time, I was the new guy in the village, so it was all a bit tentative.”

But when the footage of the foxes was shared on social media, others came forward to volunteer their gardens for the night watch. As more footage was shared, the ‘wolves’ were joined by badgers, mice, rabbits and more.

For Cairns, it felt like the start of something valuable in a village that, for too long, had become more accustomed to endings rather than beginnings.

Industrial past

Like so many former mining communities, Coalburn has not always had an easy time of it. Its story is one of boom, bust and periods of adjustment as the industries that had once employed so many locally fell away.

Lying on the Coal Burn, a tributary of the Douglas Water that flows into the River Clyde near Lanark, the village grew initially in the 1850s as a railway settlement serving the many local coal mines. The rich seams of coal that lay deep beneath the surface brought employment to the area right up to the closure of the last deep mine in 1968.

While many local miners moved away, seeking work in coalfields elsewhere in the country, others remained but changed industry, working instead at the giant Ravenscraig steelworks that had opened in nearby Motherwell.

However, the area was not yet finished with mining. Some 20 years after the last coal was brought up from deep within the ground at Coalburn’s Auchlochan No.9 pit, work began on the extraction of coal much closer to the surface at nearby Dalquhandy – at the time, one of the largest opencast mines in Europe.

Other similar operations followed, as did a range of associated infrastructure: a new washing plant to screen and clean the coal, plus road networks to carry lorries laden with coal to transport their goods to a rail terminal at Ravenstruther.

While not all had welcomed the arrival of opencast mining – a particularly environmentally destructive form of extracting coal from the ground – it did bring valuable jobs to the area for two decades. But when these operations also closed and mining withdrew from the area altogether in 1992, it left behind not just a shattered local economy but also a barren, broken landscape.

Given this industrial past, there’s no escaping the fact that the natural environment here has taken a beating. But look closer and, little by little, this is a landscape, so intensely modified by opencast mining, that is beginning to heal.

Over time, Forestry and Land Scotland acquired over 1,000ha of land locally and progressed a programme of commercial forestry planting, while a community woodland is now beginning to rise from the sterile surroundings of the main opencast mine site.

However, much of the smaller scale work that Cairns and the numerous other community groups in Coalburn are involved in has been fuelled by a very different industry. A proliferation of wind farm developments in the area – including on Hagshaw Hill to the south, Scotland’s first commercial wind farm – has brought a significant amount of community benefit funding to the area. And it is this which is now being used to affect positive change.

Step by step

Cairns smiles when remembering his first encounter with the Watch and Grow group during the height of the pandemic. “I remember being invited along to an online meeting to learn more about the group and by the time I switched off my laptop I had become its Chair,” he laughs.

As we speak, his kitchen table is buried beneath building kits for growing chillies and onions, with seeds, bulbs, dibbers, netting and bags of compost scattered around. “Then and now, I felt that if we could get more community engagement through gardening it would be a natural link into nature and wildlife,” he says. “Our aim is to improve the local environment through encouraging plant- and wildlife-based projects.”

Such small, incremental steps were important for a community whose relationship with nature was almost as scarred and weary as that of the landscape itself. For many, it was not so much a disconnection from nature as simply being unaware that there was any local wildlife at all.

Awareness was the first change to implement – something that was helped through conversations with older residents of the village. Many recalled how it was before the opencast mine, when the bird life in the area was remembered to have been rich and varied.

“I found that very useful as I wanted to bring suitable habitat back into the village so that we could attract more bird species. These guys were able to tell us what used to be here and helped us make decisions around what to plant and where.”

“Our aim is to improve the local environment through encouraging plant- and wildlife-based projects.”

Cairns Galbraith

From the start, engagement was key. The trail camera idea captured imaginations, while residents also jumped at the chance to grow wildflowers to attract pollinators when Watch and Grow secured funding from the local Community Council to give away seeds.

A further micro-project saw Watch and Grow and another local group, the Coalburn Community Action Group, work together with children from Coalburn Primary School to improve an existing nature trail that runs for a short distance along a stretch of the dismantled Caledonian Railway.

The trail was turned into a vibrant wildlife corridor with planters packed with pollinator-friendly plants, the installation of bug houses and bird nesting boxes fitted in surrounding trees.

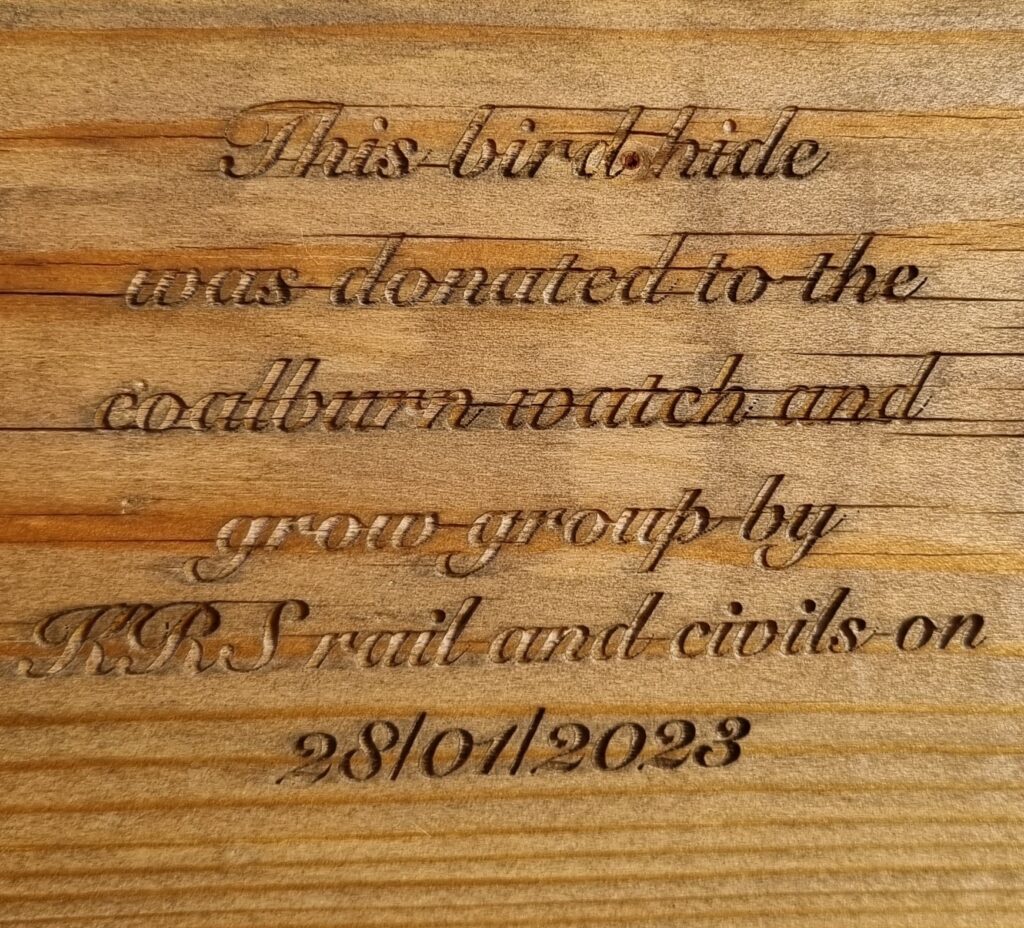

And as is often the way in small communities, one thing led to another. With support from Galawhistle Wind Farm community funding, Cairns worked on a project with Glasgow-based KRS Rails & Civils to build the Coalburdy Hut – a brand-new community bird hide at one end of the nature trail

Opened in 2023, it has already become a much-loved community asset, and not just for enjoying the return of birdlife to the area. “I received a message from a local parent who said she would often drop her kids off at school and then go to the bird hide, open up the hatches and just sit and watch the world go by,” explains Cairns.

“She had no previous interest in birds but just found it very relaxing – her moment in the day when she could escape from everything and just empty her head.”

Nextdoor Nature

When the Scottish Wildlife Trust launched its Nextdoor Nature Pioneers Programme, the first cohort of a dozen participants came from across Ayrshire, Renfrewshire, Lanarkshire and south Glasgow.

It was a perfect fit for Cairns who applied and was accepted on a programme that began in January 2023 and ran for six months. “It was a totally new programme so I guess in a way it was a bit experimental, but I got a huge amount out of it,” he says.

He was also surprised by some of what he learned. Already knowledgeable about the natural world, what he found most beneficial were the more people-focussed elements of the programme – the modules on team building, how to engage with the community and attract volunteers for projects.

“Up to that point we had just been using a Facebook group page but not everyone wants to be visible on social media,” he notes. “One module discussed how there would be interested people out there who are not on social media and covered how best to reach them.”

So, how did that translate to further efforts on the ground in Coalburn? Sometimes, it involved just going back to basics. “I went round chapping doors to introduce myself and explain what we were doing,” says Cairns. “It was just another way of mobilising people.”

And making such personal connections has generated all sorts of interesting, and related, opportunities. Cairns was approached by members of the Coalburn Horticultural Society, a local group that for well over a century had organised an annual ‘Flower Show’ that brought the whole community together. “I didn’t know it at the time but there were several national champions in the village,” says Cairns.

With no annual show since the pandemic and dwindling numbers, Cairns was asked whether Watch and Grow could help boost the membership. The result is a close working relationship that has brought young and old together. In one creative tie-in, Watch and Grow sourced seeds from the official 2023 World’s Tallest Sunflower and offered them to local schoolchildren to see whether they could grow sunflowers to match the impressive height.

This fun, competitive growing will continue to thrive as part of the Flower Show each August, with a new class introduced specially for the children involved.

“I’m not sure such a project would have happened without being involved in the Pioneers Programme,” believes Cairns. “Just being encouraged to engage more with the wider public and that whole networking side has made a big difference.

“It also made me think about who we were not reaching, from the elderly to those who are less mobile and can’t make meetings or events – those members of the community who we were, unintentionally, excluding.”

I’m not sure such a project would have happened without being involved in the Pioneers Programme.

Cairns Galbraith

Making a difference

Nature restoration does not happen overnight. Nor does recognising its value. But change is being seen in Coalburn, not least at the bird hide where feeders, that are topped up regularly by Cairns, continue to attract a host of wild birds.

Depending on season, bullfinches, siskins, hawfinches and greenfinches are now regulars, while the local population of goldfinches has skyrocketed.

But while the feeders enable people to enjoy the comings and goings of wild birds, they are not overly ‘natural’. So, the ambition now is to continue planting up native species such as rowan and hawthorn to provide habitat that can sustain the returning birds, without relying on feeders.

Elsewhere, more areas have been planted with wildflower seeds that will in turn attract insects which then provide food for the birds. “It’s all still small-scale but important – it’s about creating a foundation,” says Cairns.

And there are also bigger, more ambitious plans on the horizon – one involving people, and one involving place. For now, much of the ongoing maintenance and development of projects is reliant on Cairns and the Watch and Grow volunteers, but that is not sustainable in the long term. “I’ve got a challenging full-time job as an area manager in Glasgow, with a 90-minute commute each way, so this is all being done in my spare time,” he explains.

As such, he is now investigating what funding might be available for taking on a skilled individual who could not only take care of ongoing maintenance around the nature trail and bird hide, but also pick up on a lot of the engagement and educational work currently carried out by a small band of volunteers. “It’s the missing piece of the puzzle,” says Cairns.

Conscious also that the bird hide and nature trail appeal to just a proportion of village residents, there are now also efforts to create a larger development with the potential to touch many more in the community.

Working together with the Coalburn Horticultural Society, Watch and Grow is exploring the possibility of an asset transfer of a local-authority owned parcel of wasteland in the Timbertown area of Coalburn. The plans are at a very early stage but, using available windfarm community benefit funding, there is a very real opportunity to create a mixed-use area that includes facilities such as allotments, a communal polytunnel and a small café that would appeal to local walking groups who make regular use of the footpaths that pass close to the back of the land.

“That’s the big goal on the horizon,” says Cairns. “Such a development could connect many different interests. It’s just the kind of circular thinking that I learned so much about on the Pioneers Programme.”

We’d like to thank Cairns Galbraith for his involvement in capturing this story.

Images courtesy of Martin Shields and Jo Foo Wildlife Photography.