Sea change

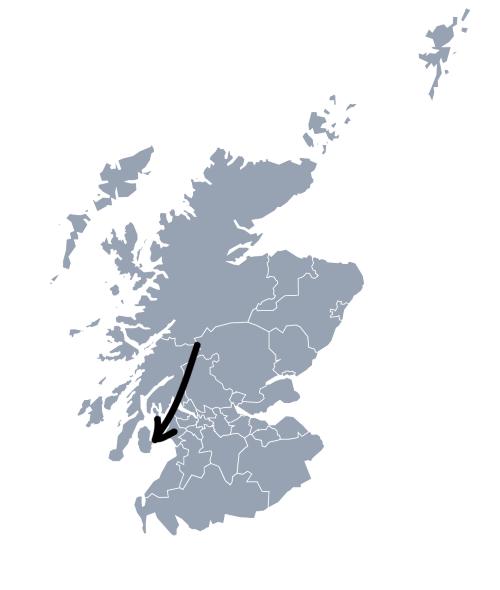

The Community of Arran Seabed Trust (COAST) was established in 1995 by two local divers with the aim of reversing an alarming decline in the health of Arran’s marine habitats.

In 2008, following years of public engagement and extensive political campaigning, COAST celebrated the creation of a community-led No Take Zone in Lamlash Bay – still the only one if its kind in the UK. Eight years later, COAST played an integral role in establishing the first community developed, and legally enforced, Marine Protected Area in Scotland.

Today, it is an internationally respected marine conservation organisation that continues to work with the local community, scientists, fishermen and government to raise awareness, support research and promote policy change around marine issues in Scotland. And it all began with a grassroots campaign led by just two people with a passion for the sea.

Average reading time: 20 minutes

For Jenny Crockett, it all began with a lobster.

And a big one at that. It was summer 2015 and she had come to the Isle of Arran to help survey the seabed around the island’s No Take Zone in Lamlash Bay. Established seven years previously, this small area of around 2.6km² was created to enable marine life to recover from the ravages of unsustainable fishing practices.

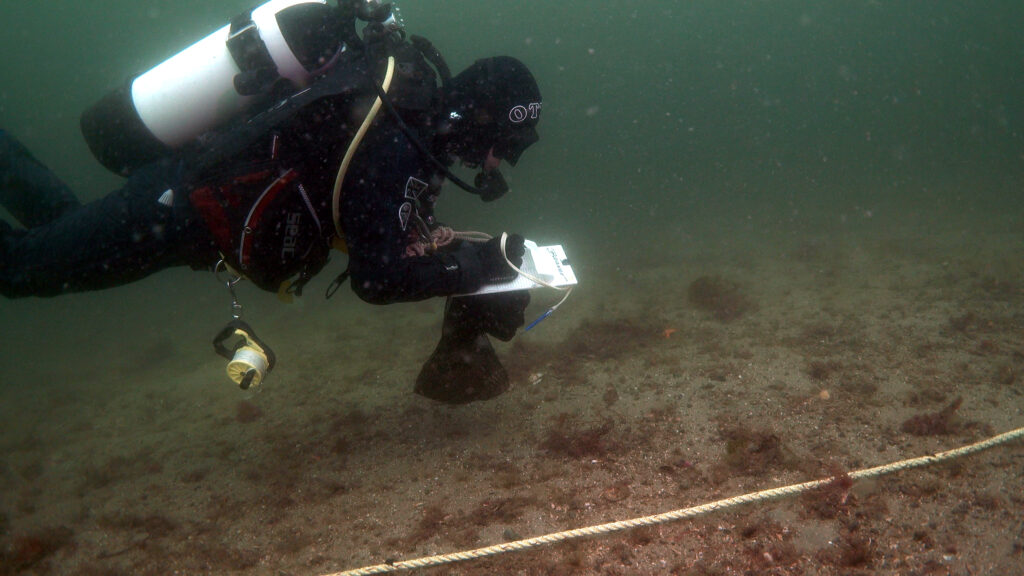

An experienced diver and research scientist, Jenny’s role was to gather baseline records of seabed health to help the Community of Arran Seabed Trust (COAST) evidence the case for enforcement measures in the recently designated – and far larger – South Arran Marine Protected Area (MPA).

To help familiarise her with local waters, Jenny was first taken on a series of dives within the No Take Zone. “I was astonished by the amount of life, including my first sighting of what was a huge lobster,” she remembers. “It was hiding in amongst boulders covered in hydroids and sea squirts.”

Almost a decade on, and now Outreach & Communications Manager at COAST, it is a moment that remains as vivid in her mind as ever. “It was a revelation,” she says. “It was then that I realised that Scottish seas could be just as colourful and biodiverse as tropical ones.”

Most of Jenny’s work that summer took place beyond the No Take Zone around the newly designated MPA. Over two months, she undertook more than 20 transect dives, each time putting down a 50m weighted line equipped with a camera fitted to calibrated laser pointers that recorded every living creature found in each survey area.

The difference between these dives and her introductory ones was night and day. “We hit sites that were almost barren, with visible trawling and dredging scars from when the site had been recently fished, and the seabed littered with broken shells,” recalls Jenny.

In other areas that had been fished less recently, key food chain species had begun to return. “There was the odd starfish here and there but little else. The survey dives revealed not just the damage being done to the seabed but also the prolonged recovery faced by the habitats and species impacted by destructive fishing.”

While significant progress had been made with the establishment of a No Take Zone, it was clear that much more protection was needed, and over a far greater area, if Arran’s seabed and coastal waters were to recover in a truly meaningful way.

Rapid decline

Talk of No Take Zones, MPAs and the recovery of inshore waters must have seemed fanciful in the mid-1980s when two local scuba divers, Howard Wood and Don MacNeish, began to witness the destruction being wrought on the seabed by bottom-towed commercial fishing practices.

The two friends – Howard a horticulturist by trade, Don a metalworker – had dived Arran’s species-rich waters since the 1970s. “Back then, they were a source of wonder,” remembers Howard.

Surrounded by the Firth of Clyde, Arran was once home to around 100 family-owned fishing boats, with small-scale traditional fishing a source of livelihood for generations of islanders. Renowned for its stocks of cod, haddock, herring and turbot, the Clyde was one of the most productive fishing grounds in Europe.

Such was the bounty of local waters that Arran hosted prestigious sea angling events, including the annual Lamlash International Sea Angling Festival which drew hundreds of anglers from across Europe.

That all changed following the UK Government’s removal in 1984 of a ban on inshore trawling within three miles of the UK coast. A rapid decline in fish stocks set in. At the last international sea angling festival on Arran, held just a decade later, catches were down by 96%.

As stocks of whitefish collapsed, so the industry turned to bottom-dwelling scallops and prawns – the last remaining marine resources – using practices that could not be more ecologically damaging.

Bottom trawling for prawns involves dragging large, weighted nets across the seabed. It can be horribly indiscriminate, with many non-target species (or bycatch) caught in the process. Dredging for scallops is even more destructive. Heavy, toothed dredges are dropped to the seabed where they dig into the underlying strata and rake it clean. This ‘gear’ is robust enough to be towed over most seabed types, including areas of rocky reef.

The net effect is that corals, kelp forests, seagrass meadows and other habitats that sequester vast amounts of carbon and provide nursery grounds for an array of fish, including commercial species, are left torn and broken – to the further detriment of small-scale fishers such as sea anglers, creelers and hand divers.

At first, seeing the loss of anglerfish, sole, rays and other once commonly spotted species, Howard and Don just shrugged their shoulders in disbelief. They could see the damage being done but felt powerless to prevent it.

But inspiration can come from many sources – even those very far away. Every few years, Don would visit family in New Zealand and it was on one of those trips, in 1989, that he met with a man who ignited an idea: Dr Bill Ballantine. Based at the Leigh Marine Laboratory, the marine research facility for the University of Auckland, Bill had campaigned for the establishment of New Zealand’s first marine reserves a decade before.

Don returned to Arran fired up. There was a better way, he thought. A later trip to New Zealand left him in no doubt that this was the direction to go in. With Howard equally enthused, the pair committed to exploring the viability of trialling a marine reserve in Arran’s inshore waters.

“Back then it was about two guys who enjoyed being in the sea and who had a desire to protect what they loved,” explains Jenny. “They found an example they saw as replicable and set out to preserve the marine habitat for future generations. That was the humble beginning of COAST.”

Bay of plenty

A sheltered spot in the southeast of the island, Lamlash Bay is guarded at its mouth by the rugged form of Holy Island – now best known as a spiritual retreat for Buddhist monks. To Howard and Don, this enclosed bay, their local dive patch, was the obvious place to start; they knew of the life that once thrived there and felt sure it could return given help.

“When we first started talking about what we wanted to do, it seemed so simple: just close an area to all fishing and let nature recover,” explains Howard. “We were so naïve at the time. Had we known about the battles that lay ahead, we might not have got started!”

And so, in 1995, using their personal savings, Howard and Don established COAST with the ambition of reversing the decline in Arran’s marine habitats. They didn’t know it at the time but their subsequent persistence, tenacity and dogged determination would create a project involving a citizen group of volunteer activists that would not only make a huge difference for local waters but also encourage other coastal communities to take back management of their seas.

Initially, their idea was to create a marine reserve in Lamlash Bay within which an area would be set aside as a No Take Zone. To progress such plans, however, they recognised the importance of getting the whole island on board.

When we first started talking about what we wanted to do, it seemed so simple … had we known about the battles that lay ahead, we might not have got started!

Howard Wood

Howard and Don were soon familiar faces at local MP surgeries and also became keen students of marine policy planning at home and elsewhere. While much had been learned from pioneering work in New Zealand, they also studied failures in the UK, and especially Scotland. This included a proposal in the early 1990s for a trial marine reserve at Loch Sween, a fjord-like sea loch near Lochgilphead that came badly unstuck.

“The proposal itself was a good one but the way the process had been managed was completely top down,” remembers Howard. “As a result, there was a sense of imposition, with strong opposition from local people and fisheries bodies.”

It was evident from the Loch Sween experience that any such proposals had to come from communities themselves. But first, local people on Arran had to be shown what was at risk: with life below the water largely out of sight and out of mind, relatively few people knew what a healthy seabed looked like or why it was important.

As a core part of their public engagement and awareness spreading, the pair began to tell the story of how Arran’s once rich seas had been plundered to the point of no return. Howard gathered archive pictures from the good times of the great sea angling festivals and began to build his skills in underwater photography to document local habitats and species.

“At first I made the mistake of only taking pictures of pretty things – people would see an image of seagrass with a pipefish in it and couldn’t believe it was taken here,” says Howard. “But what I also needed to do was show pictures of destroyed seabeds. Over time, I built up probably the best archive of pictures in the UK showing the impact of scallop dredging on the sea floor.”

Gradually, this visual storytelling began to resonate; islanders who had never previously given such matters much thought began to understand and value the marine life in local waters. They felt pride in what they had – and cared about what more might be lost.

No can do

As well as community engagement, the fledgling COAST team soon realised that it also had to confront a history of poor management of the marine environment. In those early days, prior to devolution in 1999, it was equally apparent that there was little appetite for marine reserves from the then Scottish Office.

The value of having communities that were willing and able to offer practical solutions locally – solutions that could then be scaled up as part of a wider strategic vision – seemed lost on the powers-that-be. “Instead, we were told what was not possible and that we must wait for appropriate legislation before being able to progress our plans,” says Howard.

But the local community demonstrated rather greater openness to change. One night in 1998, Howard and Don gathered together all six Arran-based commercial fishermen – creelers and shellfish divers all – to explain their idea of creating an area closed to fishing within Lamlash Bay and how it would improve the local marine environment. By the end of the night, all understood the thinking behind the proposal.

During the discussion it became clear that a No Take Zone covering the entirety of the bay would have little support as it would prevent local angling and creeling from taking place, but it was agreed that a portion of it could be set aside.

It was suggested where the boundaries of such a zone could be placed, with a view that Lamlash Bay could be easily geographically defined, with a clear entrance and exit from either end of Holy Island making it obvious when any fishing boat had entered the area.

By this time, Howard and Don had also gathered together an influential ‘brains trust’ of pro bono advisors from elsewhere. It was a support network that began with Bill Ballantine, who advised from afar, and soon extended to other key figures, including world renowned marine scientists such as Professor Callum Roberts and Dr Julie Hawkins.

Help too came in the form of devolution. With fisheries a devolved issue, and closer proximity to decision makers in the Scottish Parliament, Howard and Don made it their business to be in regular communication with MSPs of all political persuasions. The same applied to the Inshore Fisheries Branch within the new Scottish Executive Environment and Rural Affairs Department, the Crown Estate, Scottish Natural Heritage (now NatureScot) and North Ayrshire Council.

They learned fast – about community, public engagement, use of the media, how the Scottish Parliament worked and who held what power.

Later, a further key contact was made in the shape of Calum Duncan at the Marine Conservation Society. In March 2003, Calum trained Howard and other local divers in the Seasearch methodology, equipping them with the necessary skills to survey the seabed and submit records to the national Seasearch database.

In all, the citizen science records returned from the 2003 surveys included many new discoveries: a 4km-long expanse of seagrass in Whiting Bay which was home to many juvenile fish; an expanse of reef off Pladda alive with soft corals and anemones; and areas of healthy maerl beds, a fragile, coralline seaweed that takes decades to grow, elsewhere in Lamlash Bay. All are what are now known as Priority Marine Features – species that are a priority for conservation in Scotland’s seas.

It was a citizen science project that paid dividends almost immediately, and emphasised COAST’s growing credibility and standing. The following year, COAST fought a long campaign against an application for a sewage outfall pipe in Lamlash Bay during which it provided detailed ecological information, supported by photographic evidence, of the important marine features in the bay.

As a result, the outfall pipe was rerouted – a big win that was well received by islanders. Support for the COAST cause grew, both on the island and elsewhere.

Seas for all

Looking back, says Howard, there were many defining moments, but one particular game-changer was the intervention of Tom Appleby, a specialist in environmental law and visiting research fellow within the School of Law at the University of West England, Bristol who got in touch to offer a legal analysis of the legislative frameworks that COAST was working in.

“Tom would point out to Scottish Government officials what the law actually said and demonstrated how it was possible to have a No Take Zone without changes in legislation,” says Howard. “That annoyed civil servants greatly.”

By this time, it had been driven home just how much influence the fishing industry wielded, especially in the Clyde. From the outset, COAST made a distinction between the ‘static’ fishing sector – the small-scale sea anglers, hand divers and creelers – and the ‘mobile’ sector: the prawn trawlers and scallop dredgers.

The static sector, and not just the Arran-based fishers but also associated sector bodies, were largely receptive to COAST’s thinking around protected areas in Lamlash Bay, but the powerful Clyde Fishermen’s Association (CFA), which represented trawl and dredge fishermen, was rather less so.

And so began a period of positive steps forward and disheartening steps back. Meetings with skippers from Clyde-based commercial fishermen’s associations revealed agreement on the benefits of a regeneration area that could help reinforce stocks – with some even suggesting that it would make more sense to double the size of the proposed No Take Zone to extend all the way to Holy Isle rather than just part way.

But engaging with individual skippers was very different to speaking with the CFA – with one fundamental hurdle to overcome. During meetings with government officials, it was made clear that legislation ‘allowing’ a No Take Zone would require consensus from all fishermen. And that was not going to happen. From early on, CFA representatives made it known that they did not want local communities playing any part in fishing policy. As one official memorably stated: “It is our pond.”

Speaking at the time, Tom Appleby commented: “The Scottish Government were saying ‘we don’t have to speak to you because we’ve only got a duty to act for commercial fishermen’, but of course it [the sea] is a public resource.”

Such a position was a red rag to who Howard describes as “the rebellious Arranites who dared to ask for something sensible”. In response, COAST’s team of volunteers redoubled efforts to lobby MSPs, MPs and local councillors, in turn generating ever greater media attention around a message that the sea was a common resource for all, not just the powerful fishing lobby.

Finally, following 13 long years of campaigning, building community and scientific support, plus a near unanimous Scottish Government public consultation in favour of the proposal, designation day arrived: on 20 September 2008, a No Take Zone covering the upper third of Lamlash Bay came into force.

It became the first fully protected community marine reserve in the UK and only the second No Take Zone after Lundy Island, off the Devon coast. And to this day, it remains the only area of Scottish seabed where a full fishing closure is in place as a direct result of local, grassroots activism.

… the rebellious Arranites who dared to ask for something sensible!

Howard Wood

Higher ambition

Success at last. A sigh of relief and time to relax? Yes and no. Within days of the designation there was an incursion by a scallop dredger, with the authorities appearing powerless to take any action. Already, the next challenge was apparent: compliance and enforcement.

Marine Scotland, the public body charged with enforcement of the No Take Zone, was hampered by having just one inshore fisheries vessel for the entire coastline of Scotland. So, in typical fashion, COAST took up the mantle. A suite of volunteers learned how to report suspicious fishing activity in the area to assist Marine Scotland in enforcement of the new rules.

Monitoring of the area was required not just for compliance of the law but also in respect of the protection given to the marine life within the No Take Zone. Again, COAST stepped up, enlisting local divers and other islanders to work alongside scientists to monitor the protected area.

Transitioning from being a voluntary, community-based organisation to having an employee, an office and funding commitments was a huge step change at the time.

Andrew Binnie

In its first years, science was the priority – the kind of repetitive year on year research that is so key for building a picture of species recovery. Collaborating with leading research universities, including York, Glasgow, Stirling, Edinburgh and Napier, COAST was able to demonstrate significant increases in the abundance and diversity of marine life within and, over time, beyond the No Take Zone.

That return of life, and the years of struggle that preceded it, also created the conditions for something more. In early 2011, COAST became a constituted charity, securing funding for three years and employing Andrew Binnie as its first official member of staff. Andrew had just finished an MSc in aquatic system management as a mature student and, prior to that, had worked in natural resource management around the world, including on the Isle of Eigg.

“Transitioning from being a voluntary, community-based organisation to having an employee, an office and funding commitments was a huge step change at the time,” recalls Andrew, who remains on COAST’s community advisory panel today.

The main thrust of his role soon became clear. With the Scottish Government having committed to the designation of MPAs around Scotland, it was mooted that COAST might explore the idea of a third-party proposal for an MPA around the south of Arran.

With the No Take Zone already attracting increasing numbers of recreational divers, it was considered a move that could potentially benefit not just sustainable fisheries but also tourism on the island. “I felt we should be part of that process and almost immediately started working on a proposal,” says Andrew.

The initial thinking was for an MPA to cover the remainder of Lamlash Bay, but Andrew sensed an opportunity for greater gains. “Part of my job was to scale up the ambition for the MPA,” he explains. “I suggested that we put in a proposal, which is almost what we arrived at in the end, going out to three nautical miles around the whole of the south of Arran.”

Such a proposal was a challenge as COAST did not at the time have research records for the entire area. However, with many more survey dives providing meticulous data, plus additional survey records from NatureScot, it was able to back up a proposal for a nature conservation MPA based on an even wider range of priority marine features that had previously been identified.

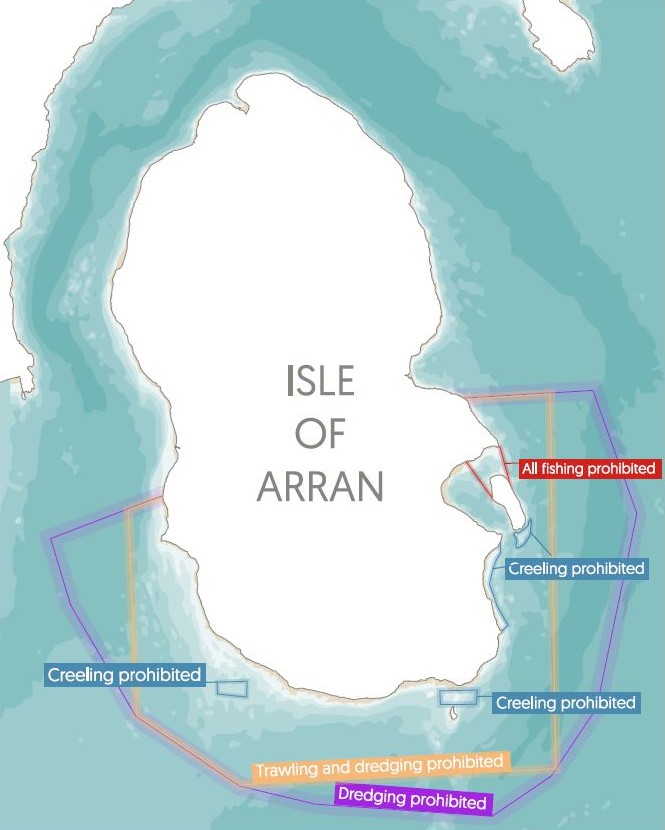

When the South of Arran MPA proposal was submitted in May 2012, it contained different levels of fishing restrictions: a ban on scallop dredging across the entire area; a ban on prawn trawling in all but a few outer edges; and four areas that banned fishing altogether due to the presence of marine features that required an extra level of protection.

Three of those areas contained maerl beds that are sensitive to any kind of bottom impact fishing, while a fourth area just off Whiting Bay is home to one of the largest known seagrass meadows in the Firth of Clyde.

In July 2014, the Scottish Government announced 30 new MPAs in Scotland including the South Arran MPA. Covering an area of around 280km2, it became the first and still only community developed MPA in the country.

But while delighted, designation was only half the battle; like so many of Scotland’s MPAs – then and now – the South of Arran MPA was a ‘paper park’ only. “You can designate an area but if there is no management of it and enforcement then it makes little difference,” notes Andrew.

Once again, COAST led community education efforts and rallied locals to keep the issue high on the political agenda. In the end, some 14,000 signatures raised in support of the proposal, a compelling evidence base and strong media interest was enough to fend off resistance from the mobile fishing sector.

Two years later, following continued seabed surveys to evidence the importance of enforcement – including the dive when Jenny Crockett eyeballed her first lobster – the MPA was finally legally enforced.

Multiple benefits

Much like the No Take Zone, having the South of Arran MPA in place matters to people on the island. “There’s a sense of accomplishment and empowerment,” believes Andrew. “We are not just sitting here watching scallop dredgers wreck our seabed.”

It has also helped put Arran on the map as a marine recreation hotspot, with all the economic benefits that tourism brings. A shore-based dive school now operates within the MPA, while two sea kayaking businesses have started up. Lamlash Bay is also the start point for the popular Isle of Arran Snorkel Trail, created together with the Scottish Wildlife Trust as part of its Living Seas programme.

This ‘mainstreaming’ of marine conservation, making it accessible to all, took another leap forward in 2018 when COAST renovated an old pavilion to create Scotland’s first MPA visitor centre.

Overlooking the Lamlash Bay No Take Zone, the Discovery Centre is a true hub, telling the story of COAST, enthusing all who come through its doors about the marine environment and serving as a research base. “Having a physical presence like this helps us demonstrate how everyone has a stake in our seas,” says Jenny.

The MPA has opened other doors of opportunity. COAST officially launched a custom-built research boat, RV COAST Explorer, in May 2023. In her first summer, she was used for public citizen science projects as well as charters for research scientists from around the UK.

Having the vessel has also created direct employment in the community. “Our skipper, Euan Ribbeck, was working away because of his job, while his wife and children were on Arran,” says Jenny. “Taking on the role of skipper has allowed Euan to live here permanently with his family.”

And in a neat tying together of island connections, Euan’s father-in-law is none other than Don MacNeish, COAST’s tireless co-founder who now serves as one of its first official ambassadors.

Next steps

Almost 30 years on from Howard and Don’s initial efforts to protect their local waters, the COAST story resonates far beyond the shores of Arran. The project has collected a host of environmental awards and accolades, with one in particular standing out: in 2015, Howard became a proud recipient of the Goldman Environment Prize, the world’s most prestigious award honouring grassroots environmental activists.

It was an award that put COAST on the international stage – with the prize money also helping pay for the establishment of the Discovery Centre. In what was a memorable year for Howard personally, he was also awarded an OBE in 2015 for services to the marine environment.

And around Scotland, COAST’s work helped inspire the formation of the Coastal Communities Network, a platform of community-led groups all committed to the preservation and safeguarding of Scotland’s coastal and marine environments.

Facilitated by the conservation charity Fauna & Flora International, and now comprising almost 30 partner groups, it’s an example of how others have felt empowered to increase grassroots participation in marine management.

Meanwhile, back on Arran, the COAST team continues to push for the most effective model for managing its own waters. Currently, the MPA designation brings a responsibility on statutory authorities to take into account impacts on priority marine features using spatial management of fisheries – in other words what fishing activities can take place and where.

Although an important first step – and more than most Scottish MPAs have in place – there remains no limit on what people can legally take from fishing activity within the MPA and, crucially, no proper understanding of what that level of take might mean in terms of providing for fisheries in the future.

“There is no action from the Scottish Government to develop a site-level management plan for MPAs around Scotland, so that’s on us,” explains Lucy Kay, COAST’s MPA Project Officer, who is currently working on a community-led plan for protected areas around Arran.

“When well-managed, MPAs are about research, monitoring and compliance, with all three properly resourced. But we are still a long way from that.”

Together with other coastal communities, COAST is now calling for tracking to be fitted to all fishing vessels irrespective of their size or gear. “We’d also like the development of a public portal that shows where vessels are fishing, as is the case in countries such as Norway,” adds Lucy. “As the sea is a public resource, the public should be able to see how it is being exploited.”

And as a member of the growing Our Seas coalition, COAST continues to push for a reintroduction of an inshore fishing limit around Scotland. “It was there before and should be there again,” believes Howard, who has recently retired from COAST’s Board of Trustees. “Scotland has committed to meeting a new Global Biodiversity Framework by 2030 but will get nowhere near it unless it brings in an inshore limit or closes significant areas to bottom-towed gear.”

So much has changed, but so much remains the same. For Howard and the COAST team, the work has only just begun.

As the sea is a public resource, the public should be able to see how it is being exploited.

Lucy Kay, COAST MPA Project Officer

Visit the Community of Arran Seabed Trust website to find out more.

All videos and images courtesy of Howard Wood and COAST.